Which is the ultimate list of artifacts in Biblical Archaelogy? So as we all know the Middle East is rich with many archaeological finds. In fact, some of them have a strong link to what we read in the Bible. For example, the names of some of the figures mentioned in it are found in various documents, and various finds are identified as belonging to events described in the Bible.

The later the finds, the more they can be cross-referenced, usually, with additional sources, and get a more complete historical picture. Formulate clear conclusions about it, and most of the assessments in the study are based on indirect findings and conclusions. So here is the ultimate list that includes all the prominent archeological items that have some significance in the study and understanding of the Bible. From the time of the patriarchs to the time of the Return to Zion.

An Introduction

Mythological and folklore stories of many peoples and ethnic groups worldwide include mythical stories about a great and destructive flood. For example, the flood in the biblical Book of Genesis; wipes out most humans and sometimes even animals. Myths of the flood are usually, but not always, part of myths of creation.

In addition, they often say that the flood was caused by a God or creator gods; who are unhappy with their initial creation or angry at their creatures for some reason. In many of these stories, a hero or a few heroes survive the flood naturally or miraculously, becoming the founders of new people or new humanity.

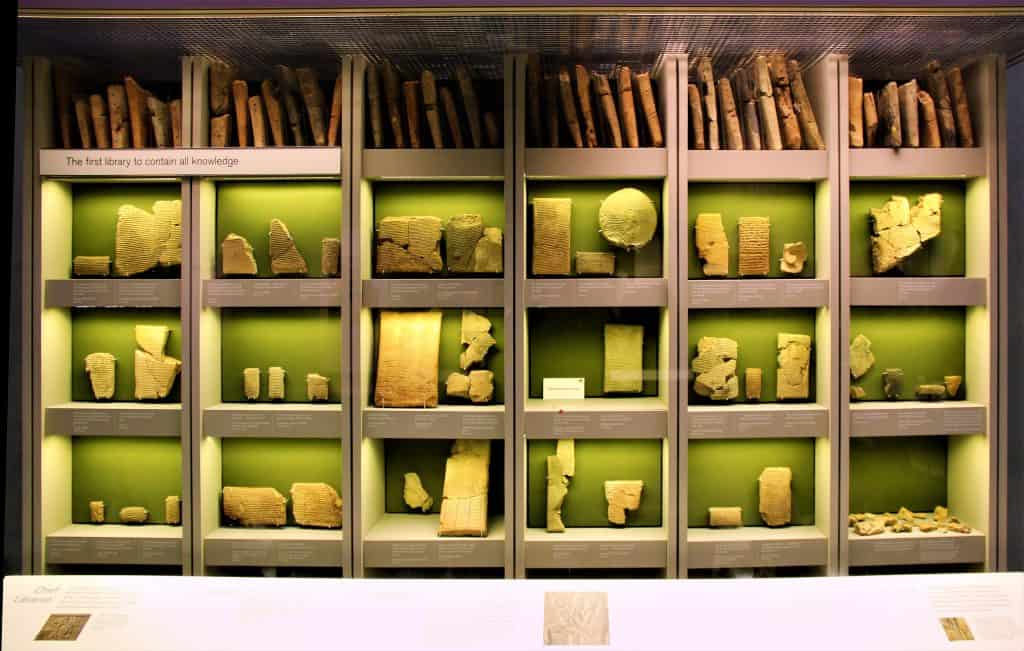

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: The Atra-Hasis Tablets

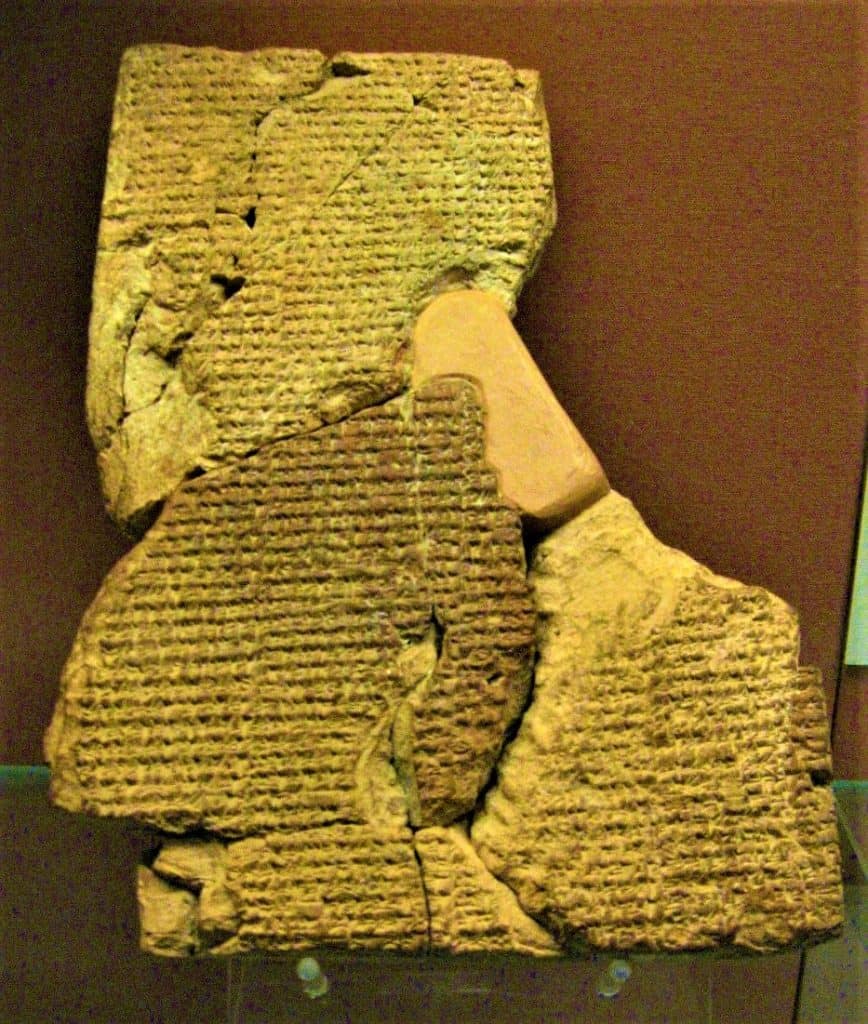

Atra-Hasis is an 18th-century BCE Akkadian epic, recorded in various versions on clay tablets, named for its protagonist, Atrahasis (‘exceedingly wise’). The Atra-Hasis tablets include both a creation myth and one of three surviving Babylonian flood myths.

The three clay tablets are written in cuneiform in the Akkadian language. The oldest known copy of the epic tradition concerning Atrahasis can be dated by colophon (scribal identification) to the reign of Hammurabi’s great-grandson, Ammi-Saduqa (1646–1626 BCE). However, various Old Babylonian fragments exist, and the epic continued to be copied into the first millennium BCE, containing a version of the story of the Mesopotamian flood, known from other ancient documents from Mesopotamia.

This Story is a Major Influence on the Biblical Story of the Flood.

In the Mesopotamian story, the god Enlil brings down a flood on the earth. But the god Enki warns the hero of the flood and provides him with detailed plans for building a huge boat, to which the hero also brings his family, animals, and birds. The boat rests on the summit of Mount Nisir, the hero sends birds to find out if the water has cleared, and sacrifices thanks to the gods. According to scholars, this story is a major influence on most of the flood myths in West Asia and the Mediterranean Basin, including the biblical story of the flood.

However, some scholars believe that comparing the stories makes a significant difference: while the story of the Flood scene stems from the usefulness and convenience of the gods whose sleep is disturbed, the biblical flood is described as a punishment for the moral corruption of mankind. The reason for the rescue is also different. Atra-Hasis was saved by his friendship with the god Enki and by a practical motive, as Enki explains at the end of the story, while Noah was saved by his moral virtue.

The biblical explanation for hard work and human suffering also raises a significant gap: in the Mesopotamian epic hard work is a destiny that stems from the nature of the world, and even the gods are subject to it. The man was meant by his creation to suffer in their place. In the Bible, however, man is condemned to hard labor only for the guilt of his sin in the story of the Garden of Eden and eating from the forbidden fruit.

Ugaritic Poetry

The discovery of the Ugaritic archives in 1929 has been of great significance to biblical scholarship, as these archives, for the first time, provided a detailed description of Canaanite religious beliefs during the period directly preceding the Israelite settlement. These texts show significant parallels to Hebrew biblical literature, particularly in divine imagery and poetic form. Ugaritic poetry later has many elements in Hebrew poetry: parallelisms, meters, and rhythms. The discoveries at Ugarit have led to a new appraisal of the Hebrew Bible as literature.

Canaanite mythological poetry, written in the Ugaritic alphabet in Ugaritic and Akkadian languages, on pottery tablets discovered in Ugaritic libraries. In the study, it is divided into several epic works: the plots of Baal and Anat, the Legend of Keret, The Tale of Aqhat, and more.

Biblical poetry has a linguistic and stylistic affinity to Ugaritic poetry, more than any other group of texts in the ancient world. Among the most prominent Biblical many found their parallel Ugaritic: “Take up the cause of the fatherless;

plead the case of the widow” (Isaiah 1:17); “Your kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and your dominion endures through all generations.” (Psalms 145); “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God.” (Psalms 42).

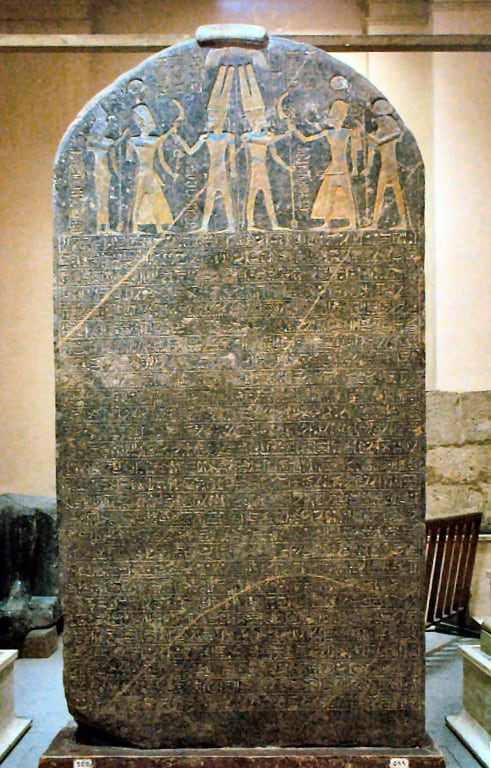

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele – also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah – is an inscription by the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah (reign: 1213–1203 BCE) discovered by Flinders Petrie in 1896 at Thebes, and now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The text is largely an account of Merneptah’s victory over the Libyans and their allies, but the last 3 of the 28 lines deal with a separate campaign in Canaan, then part of Egypt’s imperial possessions. The stele is sometimes referred to as the “Israel Stele” because a majority of scholars translate a set of hieroglyphs in line 27 as “Israel”.

The stele represents the earliest textual reference to Israel and the only reference from ancient Egypt. It is one of four known inscriptions from the Iron Age that date to the time of and mentions ancient Israel, under this name.

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: Gezer Calander

The Gezer calendar is a small limestone tablet with an early Canaanite inscription discovered in 1908 by Irish archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister in the ancient city of Gezer, not far from Jerusalem. It is commonly dated to the 10th century BCE. However, the excavation was unstratified, and its identification during the holes was not in a “secure archaeological context,” presenting uncertainty around the dating. Most biblical scholars date it to the 10th century BCE.

Scholars are divided as to whether the language is Phoenician or Hebrew and whether the script is Phoenician (or Proto-Canaanite) or paleo-Hebrew.

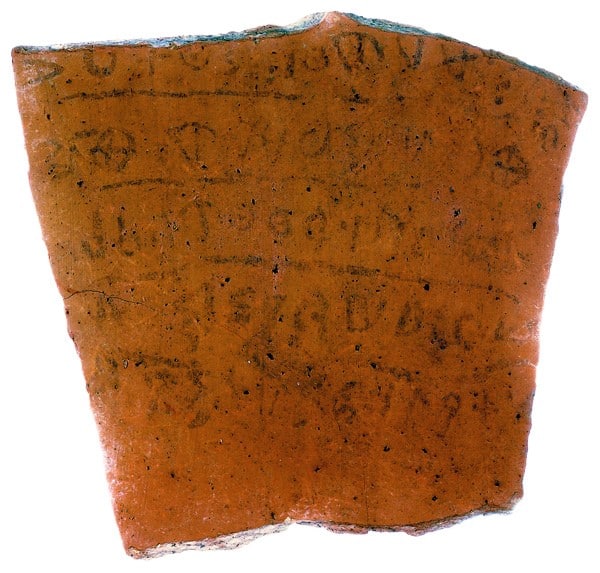

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon

During the second excavation season in Khirbet Qeiyafa (2008), an ostracon, a trapezoidal pottery fragment 16.5 cm long and 15 cm wide, was discovered. Such potsherds were in use at the time, most often as a draft for an official letter written on papyrus or parchment. However, the researchers were surprised to find the pottery in a simple structure, which is not characteristic of a library or a residence of a person from the affluent strata. At that time, it was rare to find such a find in an ordinary house.

On the ostracon are five lines written in ink, from left to right, in the Hebrew language, in a Proto-Canaanite alphabet. The inscription on the pottery includes several terms such as “don’t Do” and “slave,” which were unique at that time only to Hebrew and not to any other similar language, such as Ugaritic and more. Therefore, this ostracon is considered the oldest pottery written in the Hebrew language, proof of the existence of a Hebrew script as early as the end of the 11th century BCE – early 10th century BCE and a contradiction to the claim that many archaeologists accepted before its discovery that the Bible couldn’t have been written before about 700 BCE, due to the lack of an epigraphic find, from the time of King David for example, indicating the existence of a Hebrew script.

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: Bubastite Portal

The Bubastite Portal gate is located in Karnak, within the Precinct of the Amun-Re temple complex, between the temple of Ramesses III and the second pylon. It records the conquests and military campaigns in the twenty-second Dynasty c.925 BCE of Shoshenq I. Shoshenq has been identified with the biblical Shishaq, such that the relief is also known as the Shishak Inscription or Shishaq Relief.

This inscription is in Egyptian hieroglyphics and carries a long list of places in the Land of Israel. The inscription describes the actions of Shoshenq I, king of Egypt, in a military campaign in the Land of Israel that took place mainly in the Kingdom of Israel, in the Negev, and other areas, some with Hebrew names.

Also mentioned in the list of Shishak cities in the Kingdom of Judah, such as Givon and Ayalon. Many signs of destruction from these years were found in many cities in the country (including Lachish and Beit Tzur, which were part of the Kingdom of Judah, Beit Shean, and Megiddo, where a fragment of a stele with his name and title, and additional evidence of invasion) was discovered. Many archaeologists attribute the signs of destruction to this journey.

The Bible briefly states that “In the fifth year of king Rehoboam, Shishak, the king of Egypt, attacked Jerusalem.”

1 Kings 14:25

Also, on this journey to the Kingdom of Judah (c. 925 BC), he took the treasures of the Temple and the King’s Palace. Although a different picture is obtained, according which the main goals of the journey were not the Judea and Jerusalem Mountains (which are not mentioned at all in the inscription); but the Kingdom of Israel and the Negev Desert. Jerusalem area. Author of a book of kings on his part (at the earliest in the 7th century BCE), he drew the knowledge of the journey to Jerusalem from a temple chronicle, which dealt with the history of the Temple or relied on oral tradition.

However, according to scholars who deny the existence of the United Kingdom of Israel and the division, since Shoshenq I does not mention in the inscription the kingdoms of Israel and Judah and Jerusalem, this indicates that the two kingdoms did not exist then and that in the 10th century Jerusalem, therefore, was merely a small settlement and was not used as the capital of a great kingdom. Therefore, Shishak (Shoshenq) skipped over it, and since it indicates only cities and towns, it suggests that the land of Canaan was still divided into kingdom-cities at this time.

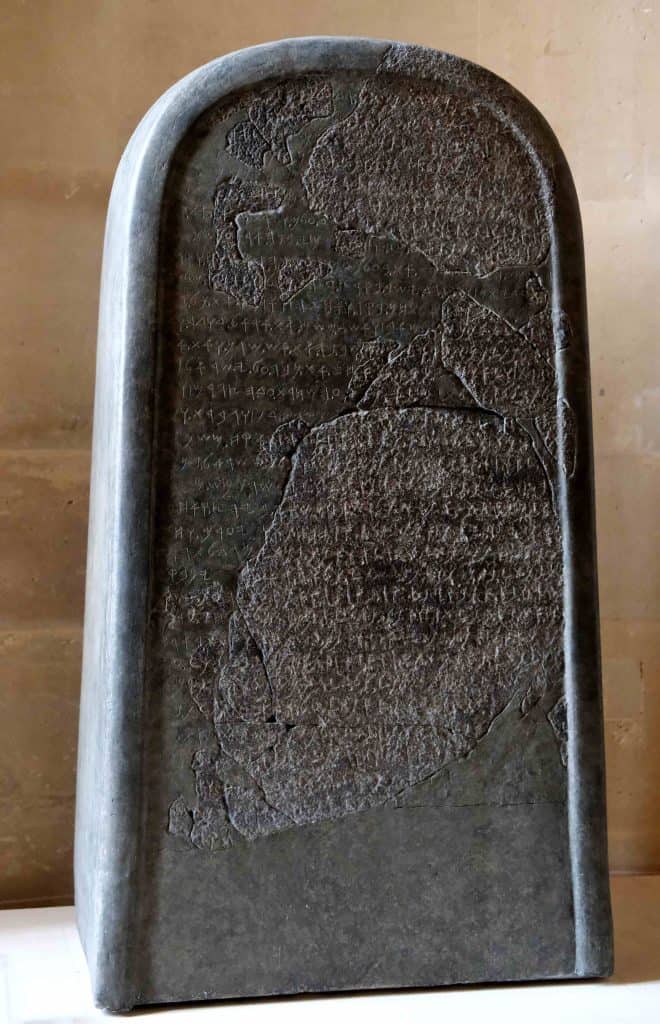

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: Mesha Stele

Today kept in the Louvre Museum, the Mesha Stele, also known as the Moabite Stone, is a stele dated around 840 BCE containing a significant Canaanite inscription in the name of King Mesha of Moab (a kingdom located in modern Jordan). Mesha tells how Chemosh, the god of Moab, had been angry with his people and had allowed them to be subjugated to Israel.

But at length, Chemosh returned and assisted Mesha in throwing off Israel’s yoke and restoring Moab’s lands. Mesha describes his many building projects. It is written in a variant of the Phoenician alphabet, closely related to the Paleo-Hebrew script. The tombstone was discovered in 1868 and is one of the most important discoveries in Biblical archeology due to being the very first archaeological find to describe events in the Bible.

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: Kurkh Monoliths

The inscription on the tombstone is an anal edition from the sixth year of Shalmaneser III, king of Assyria (853 BCE), depicting the Battle of Qarqar (inscription written immediately after the battle), in which the “Twelve Kings of the Seashore Alliance” united against the Assyrian Empire, including the kings of Aram-Damascus, Hama, Egypt, Arabia, and Byblos. Among the Allies, “the Israelite Ahab” is mentioned, who brought 2,000 chariots and 10,000 infantry to the battle (a power significantly more significant than the rest of the kings: Ahab got about 50% of the chariots) and about 18% of the allies’ infantry.

Furthermore, this large number of chariots in Ahab’s army indicates that the king of Israel was in charge of a military alliance of states in the Land of Israel and across the Jordan and the Israeli army included their armies. The Battle of Qarqar is not mentioned in the Bible. This is the earliest non-biblical testimony to the Kingdom of Israel and is the earliest known encounter of the Kingdom of Israel (or Judah) with Assyria. Additional Assyrian inscriptions indicate that Yoram and Ahaziah, the sons of Ahab, also remained allies in the Covenant of the Twelve Kings.

List of Artifacts in Biblical Archaeology: The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a black limestone Assyrian sculpture with many scenes in bas-relief and inscriptions. It comes from Nimrud and commemorates the deeds of King Shalmaneser III (reigned 858–824 BCE). It is one of two complete Assyrian obelisks yet discovered. It is historically significant because it is thought to display the earliest ancient depiction of a biblical figure – Jehu, King of Israel.