The Broad Wall is an ancient defensive wall in the Old City of Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter. The wall was unearthed in the 1970s by Israeli archaeologist Nahman Avigad and dated to the reign of King Hezekiah (late eighth century BCE). The Broad Wall is a massive defensive structure, seven meters thick. The unbroken length of the wall uncovered by Avigad’s dig runs 65 meters (71.1 yds) long and is preserved in places to a height of 3.3 meters (3.6 yds).

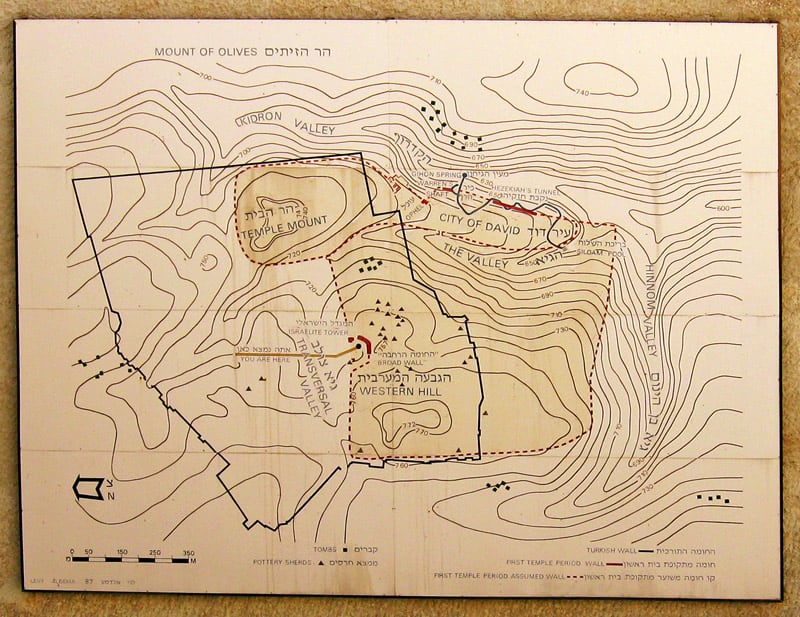

It was long believed that the city in this period was confined to the fortified, narrow hill running south of the Temple Mount known as the City of David. Avigad’s dig demonstrated that by the late eighth century, the city had expanded to include the hill west of the Temple Mount. The motivation for building the walls was Sennacherib’s expected invasion of Judea. The wall might be referred to in Nehemiah 3:8 and Isaiah 22:9–10.

9 You saw that the walls of the City of David were broken through in many places; you stored up water in the Lower Pool. 10 You counted the buildings in Jerusalem and tore down houses to strengthen the wall.

Isaiah 22:9–10.

The Broad Wall: the Debate Between the Maximalists and the Minimalists

One of the important questions in the study of the First Temple period was whether the city remained confined to the narrow confines of the City of David and the expansion of Solomon to the Temple Mount throughout the period up to the destruction of the First Temple in 587/7 BCE or whether the city expanded beyond its walls under urban and topographic conditions.

Was the city of Jerusalem in the days of the First Temple located on one or two hills? Josephus Flavius is the only historian to describe Jerusalem (Jewish Wars, IV, IV), and his testimony is valid about his time: the days of the Second Temple. He distinguishes between the upper and lower city. Still, it is not clear from his remarks when the city began to spread towards the southwestern hill, and scholars have disagreed on this subject for about a century. To resolve this issue, one has to rely on reliable information from historical sources or archaeological excavations. These two sources were not clear and quite significant enough. Two main “Maximalist” and “Minimalists” schools were formed, and each relied mainly on one of two criteria: historical or archaeological.

Credit: Tamar Hayardeni, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Broad Wall: The Approach of the Maxmilists

In the opinion of the Maxmilists, Jerusalem stretched over both hills throughout the First Temple period. They relied primarily on Josephus Flavius, describing the course of the first wall surrounding the western hill, which Josephus attributed to David and Solomon. The Maximalists accepted these things literally. The Maximalists also saw in the Bible hints that there were suburbs outside the boundaries of the City of David. The reference to the “Mishnah” and the “Maktesh” is mentioned in the Bible and is usually interpreted as new suburbs located somewhere outside the old city limits.

The Broad Wall: The Approach of the Minimalists

Compared to the Maximalists, the Minimalists argued that such a large area is unrealistic for a city in the Land of Israel in the Israelite period. In their opinion, the first wall that Josephus mentions should be attributed to the Hasmoneans. This reference is based on sections of walls from the Hasmonean period, which were exposed in the walls surrounding the western hill to the west and south. They mainly relied on negative archaeological data; no remains from the First Temple period were found on the western hill, where very limited excavations were conducted.

In the 1960s, Kathleen Kenyon excavated in Western Hill. She conducted excavations in vacant places on Western Hill and concluded that there was no settlement there during the Israeli period. Because of Kenyon’s great reputation as an archaeologist at the time, the matter was seen as a closed case. But after 1967, large-scale excavations were made possible in the ancient city, and it turned out that Kenyon was wrong. She drew far-reaching conclusions based on these basic excavations, which were conducted in a few limited pits and based on results that seemed to her to be negative. Until the eighth century BCE, Jerusalem was limited to the Eastern hill. In the eighth century, it grew three or four times its previous size.

The new settlement spread over the entire Western Hill and was initially a settlement without a wall and cut off from the main city. But later, the entire city was surrounded by a wall. The find that was conclusive evidence and tipped the scales in favor of the “Maximalists” was the find of the Broad Wall in today’s Jewish Quarter, in the upper city of Josephus, on the southwestern hill of the Old City. The excavator, Prof. Nachman Avigad, described the excitement caused by the discovery:

“Could it be a wall? The excitement was great and the tensions were high. I did not let any of my senior archaeological colleagues in the secret of things, I just did not dare, lest it be false in the end. And we must not fail to draw early conclusions, as sometimes happens. This element has been with us for months. We continued working, and the further we went we saw that it was more realistic.”

Prof. Nachman Avigad: ‘The Upper City of Jerusalem’

Analyzation of the Finds

A window of opportunity for excavations in the Jewish Quarter was opened after the Six-Day War and before the reconstruction and rebuilding of the quarter. The vast wall was found in 1970. The excavations revealed forty meters of the wall, seven meters wide. Based on the ceramic finds, the wall was dated to the eighth century BCE. Due to the unusual thickness of the wall, scholars tend to believe that it is probably the broad wall mentioned in the book of Nehemiah:

“Uzziel son of Harhaiah, one of the goldsmiths, repaired the next section; and Hananiah, one of the perfume-makers, made repairs next to that. They restored Jerusalem as far as the Broad Wall”

Nehemiah 3:8

The existence of an unwalled settlement was proved by the finding of the wall, which was partly built on the ruins of previous Israelite houses. The remains of these fortifications are located on the city’s northern boundary, which is the less-protected natural boundary. The particular course of the wall from north to south and its turn to the west can be explained by topographic reasons.

The Broad Wall: The Fortifications Project of King Hezekiah

When choosing the fortification line, the existing houses were not considered, and when necessary, the houses were demolished to make way for the wall. This situation is described in Isaiah 22:10 (see above). These were undoubtedly emergency measures taken before impending danger and in preparation for war. The war Hezekiah prepared was the journey of Sennacherib, king of Assyria, to Judah in 701 BCE. It is known that Hezekiah did two important factories before the war: fortifying the city and bringing water to the city through Hezekiah’s pool. These preparations of Hezekiah are detailed in the Bible:

“2 When Hezekiah saw that Sennacherib had come and that he intended to wage war against Jerusalem, 3 he consulted with his officials and military staff about blocking off the water from the springs outside the city, and they helped him. 4 They gathered a large group of people who blocked all the springs and the stream that flowed through the land. “Why should the kings[a] of Assyria come and find plenty of water?” they said. 5 Then he worked hard repairing all the broken sections of the wall and building towers on it. He built another wall outside that one and reinforced the terraces”

Chronicles 32: 2-5

The Jewish Quarter Ultimate Guide

After the discovery of the remains of the wall, there was a growing tendency among researchers to look for the continuation of its route on the southern and western edges of the western hill. Although clear remains from the Iron Age were exposed in the citadel, on the western edge of the Armenian Quarter, and on the edge of Mount Zion, no clear evidence of the city wall was found, and there is still no conclusive evidence to confirm the hypothesis regarding the route of the wall.

Hezekiah’s preparations for Sennacherib’s impending siege bore fruit. Jerusalem was not conquered. Whether because Sennacherib was forced to return to Assyria due to internal policy issues or the miracle of the plague as described in the Bible.